Digest - The IEA Future Of Cooling Report: Opportunities For Energy Efficient Air Conditioning

Greetings building science enthusiasts!

The IEA put out a pretty fantastic report recently on The Future Of Cooling, outlining opportunities for energy efficient air conditioning systems. The perspective of this report is excellent and the International Energy Agency has taken on a daunting task of amassing some serious data and predictive analytics to bring these findings to light. We've done our best to help you digest some of the big take aways.

“Growing demand for air conditioners is one of the most critical blind spots in today’s energy debate. Setting higher efficiency standards for cooling is one of the easiest steps governments can take to reduce the need for new power plants, cut emissions and reduce costs at the same time.”

Highlights From The Report

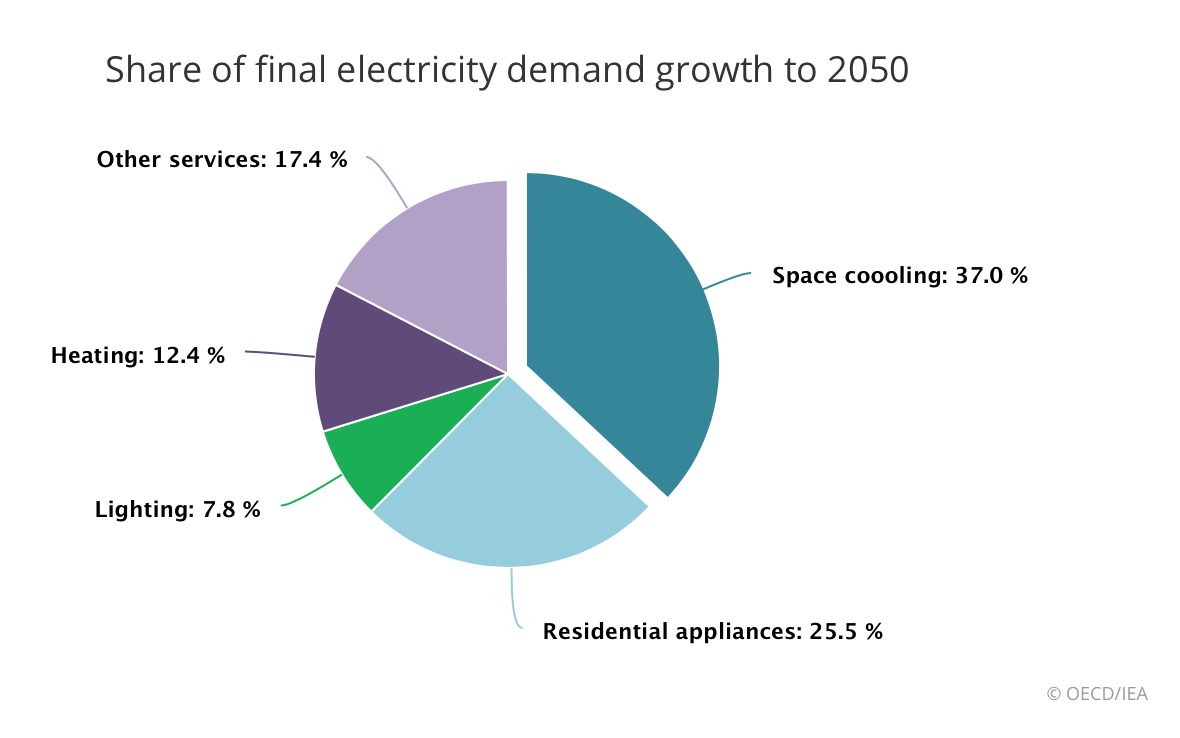

The growing use of air conditioning systems in homes around the world will be one of the top drivers of global electricity demand over the next three decades. In the IEA report – “The Future of Cooling” – they're calling the potentiality for the sharp rise in demand without new codes to effectively handle the raw energy inputs and outputs, that the the world will face a “cold crunch” from the growth in cooling demand. The logic makes sense - if air conditioners are a dominant energy user in homes and the market share grows vastly, we run into the strange trap wherein the planet is getting hotter so we try to cool down our indoor spaces, in effect adding to the warming trends.

Air conditioning today is concentrated in a small number of countries, but AC sales are rising rapidly in emerging economies. Courtesy of IEA

If as the report suggests, global energy demand from air conditioners is expected to roughly triple by 2050, this would require new electricity capacity to become equivalent to the combined current electricity capacity of the United States, the EU and Japan. This is a significant growth and one that presents a real challenge to climate solutions. And on the economic front, there will be significant movement in industry creation/expansion in underdeveloped places across the world. The global stock of air conditioners in buildings will grow to 5.6 billion by 2050, up from 1.6 billion today – which amounts to 10 new ACs sold every second for the next 30 years.

Keep in mind that none of this is specific to any type of air conditioning equipment, but assuming that the majority of growth is happening in markets where ductless VRF units (mini splits) are commonplace, we could reasonably expect to see more expansion of that technology rather than the less energy-sensible unitary compressors. But even still, there's a lot of energy infrastructure necessary to

Using air conditioners and electric fans to stay cool already accounts for about a fifth of the total electricity used in buildings around the world – or 10% of all global electricity consumption today. But as incomes and living standards improve in many developing countries, the growth in AC demand in hotter regions is set to soar. AC use is expected to be the second-largest source of global electricity demand growth after the industry sector, and the strongest driver for buildings by 2050.

Supplying power to HVAC units at a scale like this comes with substantial economic costs and environmental/ecological implications. The variability of unit efficiency and market uptake of more energy sensible units is certainly an issue. For example, HVAC units sold in the Japanese and the European markets are generally in the range of 25% more efficient than those sold in the United States and Chinese markets. Base line efficiency improvements, or codification could cut the energy growth from HVAC demand in half through more stringent mandatory energy performance standards.

The report outlines what they view as key policy actions. In what they've called an Efficient Cooling Scenario, which was designed to be compatible with the goals of the Paris Agreement (of which the U.S. is not a signing party, unfortunately), the IEA predicts that through more stringent minimum energy performance standards, the average energy capacity of the widely available HVAC units worldwide could more than double between now and 2050. The idea is that this is not only a way to curtail environmental issues, but reduce governmental spending on energy infrastructure across the globe - the saving estimates are as much as USD 2.9 trillion in investment, fuel and operating costs.

The rise in cooling demand will be particularly important in the hotter regions of the world, like Austin, TX. Interestingly, this is the least well understood climate zone type in the building science disciplines, although we're in the trenches bringing awareness to the AEC community's strong need to step up its game in hot humid climates. See, for example, The Humid Climate Conference.

I didn't expect this number, but the report calls out that less than 1/3 of global households own an air conditioner of any kind, which is rather staggering considering how normal it is in the southern US. They call out that in countries such as the United States and Japan, more than 90% of households have air conditioning, compared to just 8% of the 2.8 billion people living in the hottest parts of the world (often accompanied by humidity).

The issue is particularly sensitive in countries in high growth moments, with the biggest increase happening in hot countries like India – where the share of HVAC in peak electricity load could reach 45% in 2050, up from 10% today without sensible action at a policy level. The implications are worth seriously considering when we think about the scale we're talking about.

What's Next?

““The Future of Cooling” is the second IEA report that focuses on “blind spots” of the global energy system, following the “The Future of Trucks,” which was released in July 2017. The next one in this series – “The Future of Petro-Chemicals” – will examine ways to build a more sustainable petrochemical industry. It will be released in September.”