Environmental Design: Where Art & Science Intersect

What is Environmental Design?

Architectural design exists at the confluence of creativity and data, an intellectual space that presents hard problems to solve. What may be the best path to a high performing building may fall completely flat in the realm of inspiration. The inverse is also true — what may be an incredible feat of creative potential in form may completely lack necessary function. So how do we successfully reconcile the age old question of form and function to create beautiful, uplifting spaces that also perform across a range of metrics that benefit occupant and planet? Enter environmental design.

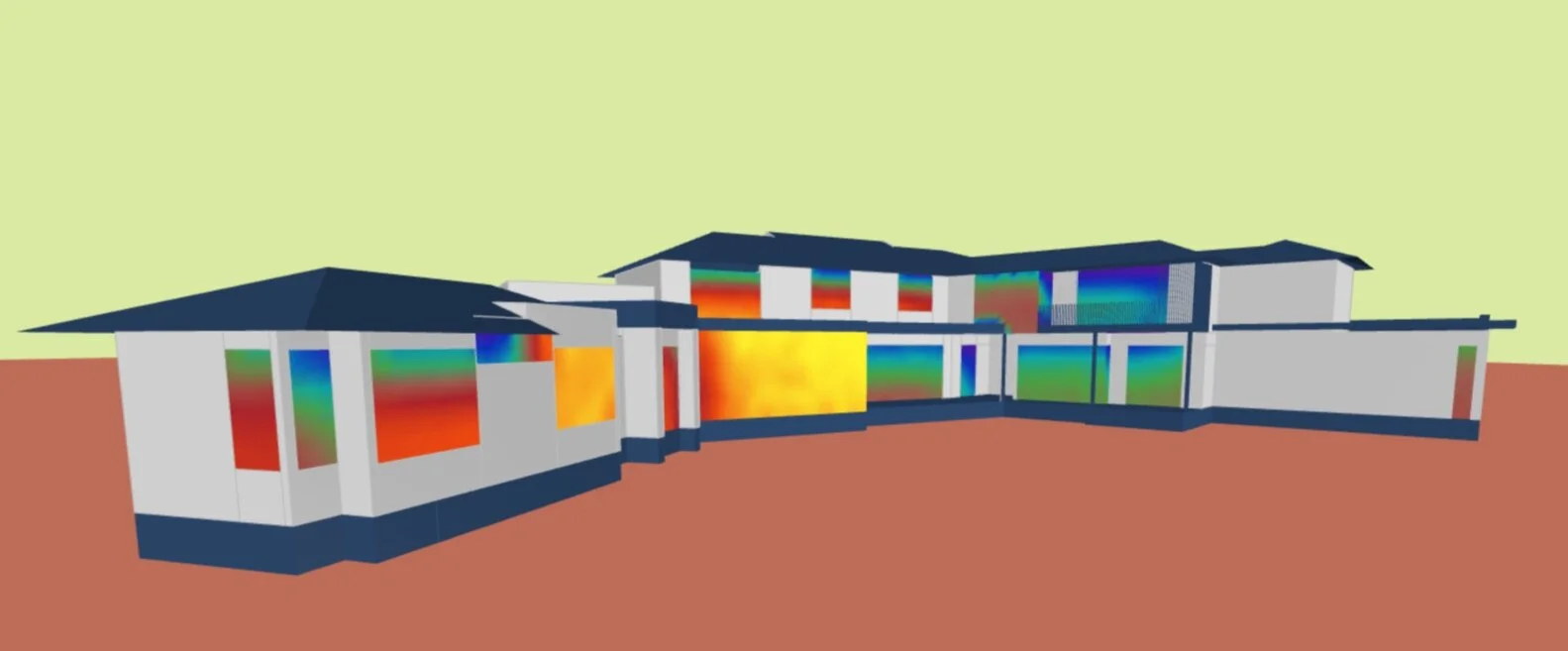

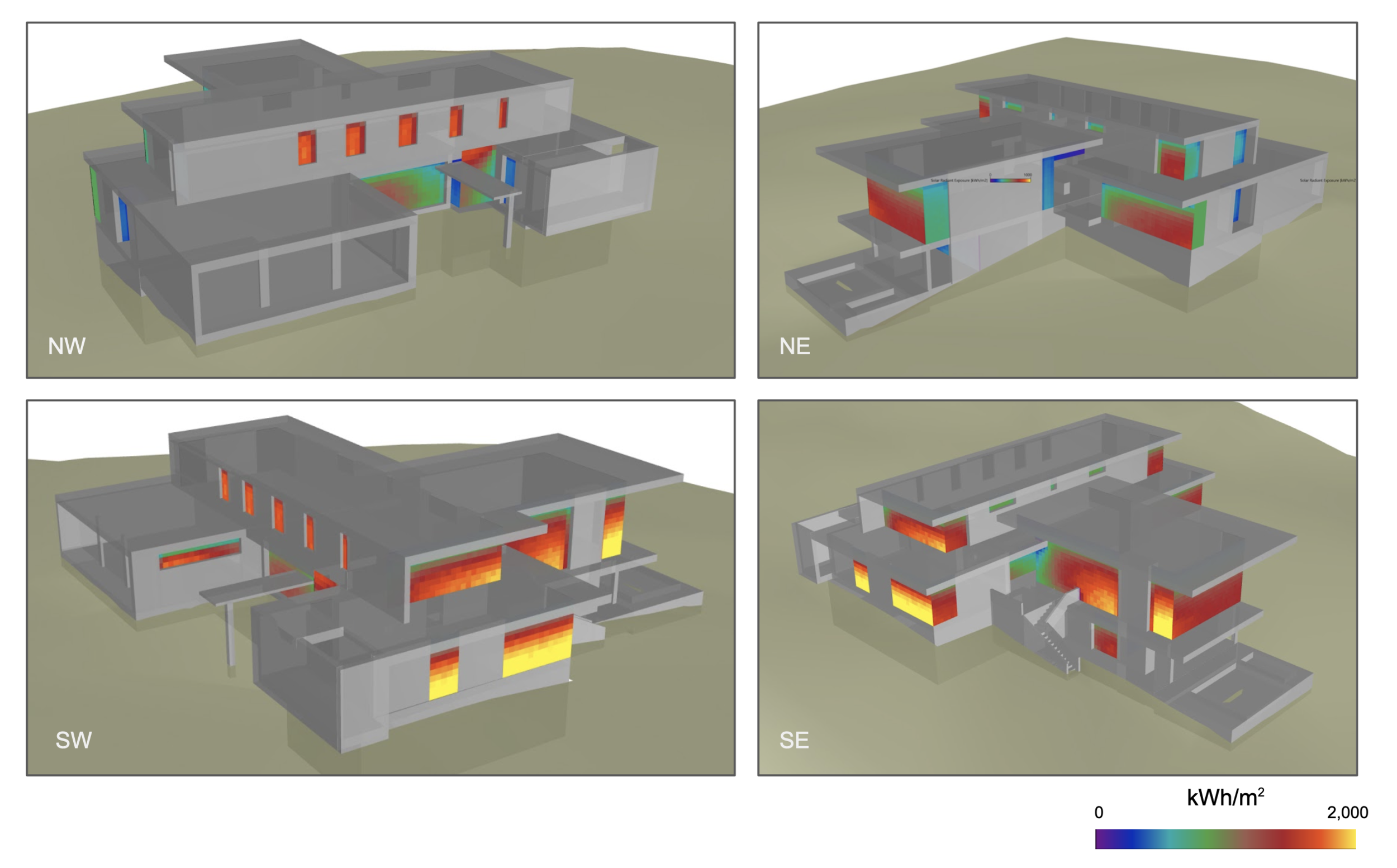

Thermal window performance visualized for a single family residence

Fundamentally, environmental design is an exercise in understanding the impacts of a given environment on a building’s performance and the experience of its occupants. There are a range of analyses that can be done to facilitate this understanding, but when these analyses happen is quite important. In the early, conceptual phase of an architectural design process, there is tremendous value in being able to iteratively test assumptions against simulated performance data, compare design options, and make informed decisions while the design is still fluid. The whole idea is to optimize a project’s architectural strategies using objective analyses of massing, orientation, fenestration, and even seasonal daylight autonomy, glare potential, and passive thermal comfort (meaning without the aid of active HVAC systems).

Why Do This?

Human beings are a fascinating, complex species. We often recognize bias in others (even relatively benign biases like a preference for a certain color or flavor), but often do not recognize biases in ourselves. Most people assume that they are objective, but forget that each of our experience is formed by perception, which is constructed by a lifetime of unique neural pathways formed in the brain. This phenomena plays out in many neurological and psychological studies. No two brains have the same neural pathways and yet each brain thinks it is the most objective decision maker it knows.

On a practical level, this dynamic is how any of us operate on a day-to-day basis; the physiological and psychological underpinnings of our perspectives and worldview. It’s the way we have evolved over hundreds of thousands of years and is quite literally a natural operating mode. But on another level, those same neural pathways that we create over a lifetime are also what can keep any of us from stepping outside our biases or changing old habits. It’s not an intellectual deficiency by any means, but rather a physical reality we each experience. The good news is that our brains are relatively plastic and flexible when trained the right way. When we intentionally shake things up, the results can be outstanding.

Bringing objective data into the decision making matrix of an architectural design is a powerful way for us to push passed cognitive biases that inform design and push our projects into new vistas of performance. Whether we think critically about this or not, our decisions impact the durability, comfort, and experience of our buildings, as well as the health impacts on occupants.

What Does It Look Like?

Architects are visual creatures. This visual orientation is a major driver behind the most stunning landmarks across the planet. And, if we’re being honest, there are few people who enjoy sifting through charts of data without a deep understanding of context. That’s exactly why we have created a service and deliverables oriented around highly visual feedback in a service we call Passive Systems Environmental Design. Seeing the performative aspects of a design concept positions a visual thinker to see clearer alternatives when needed.

Light

What better media to paint with than light? Having in hand a data-driven understanding of how light will interact with a building is an under-realized tool for many architecture firms. No longer do we need to rely on guess work.

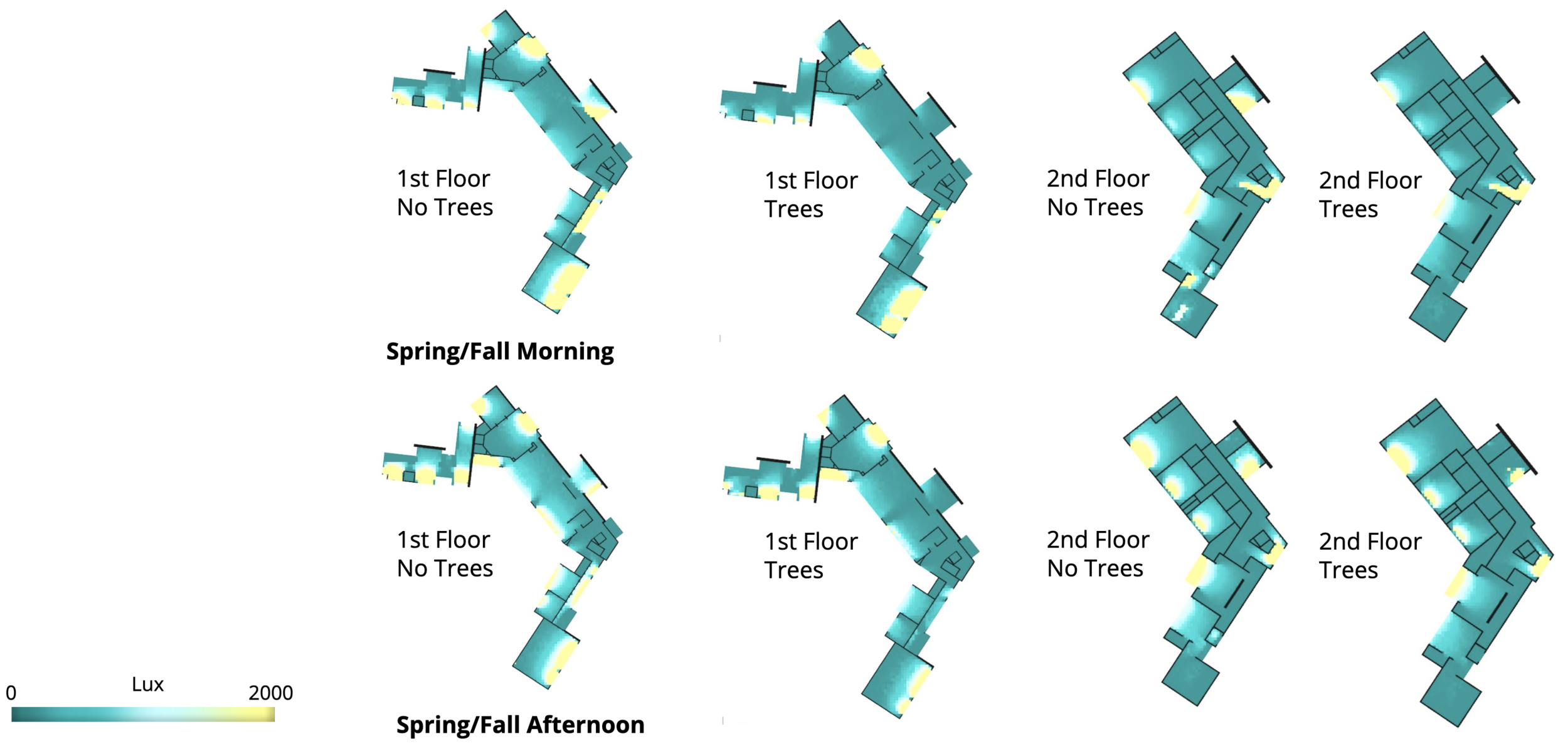

Example graphs of an outdoor comfort profile

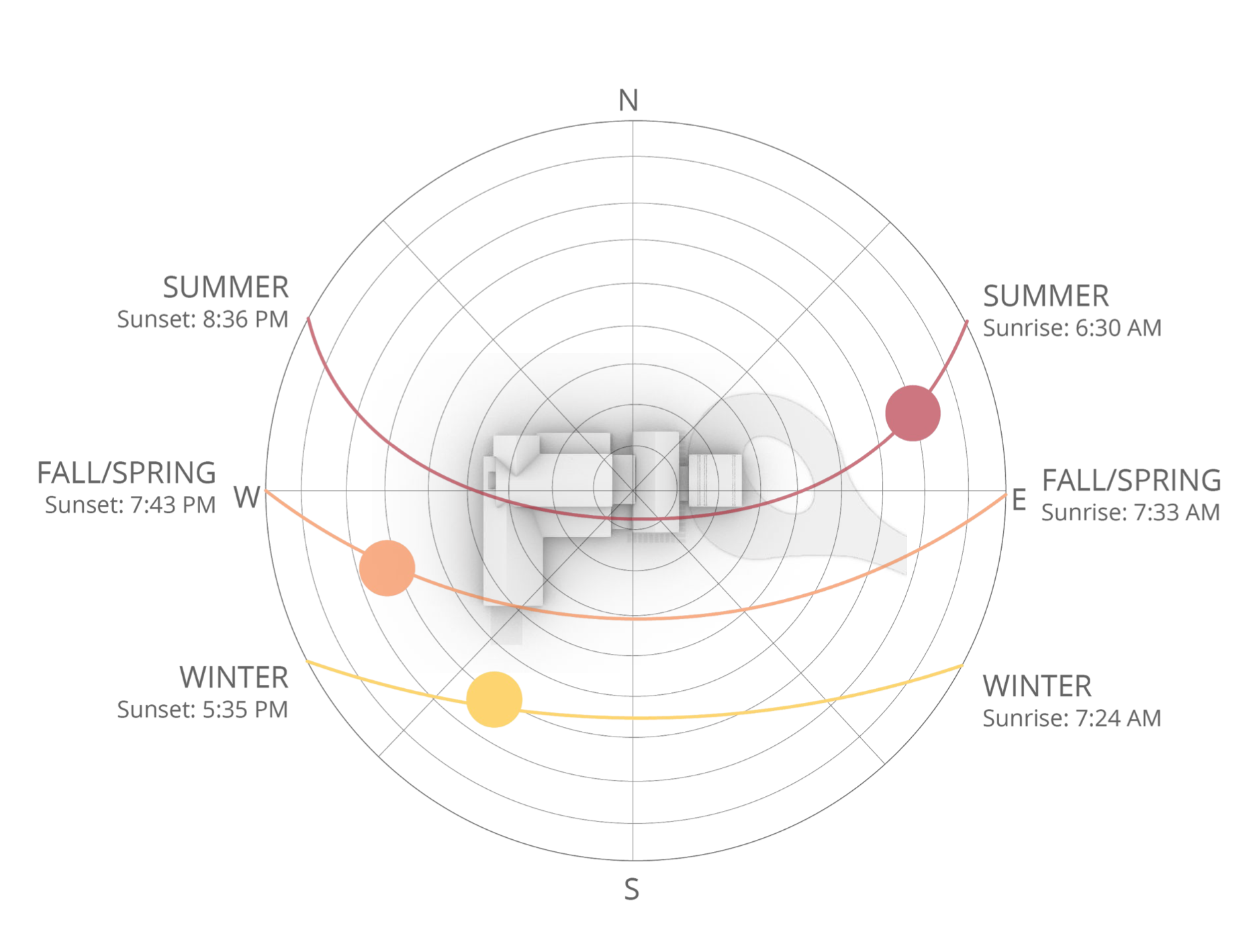

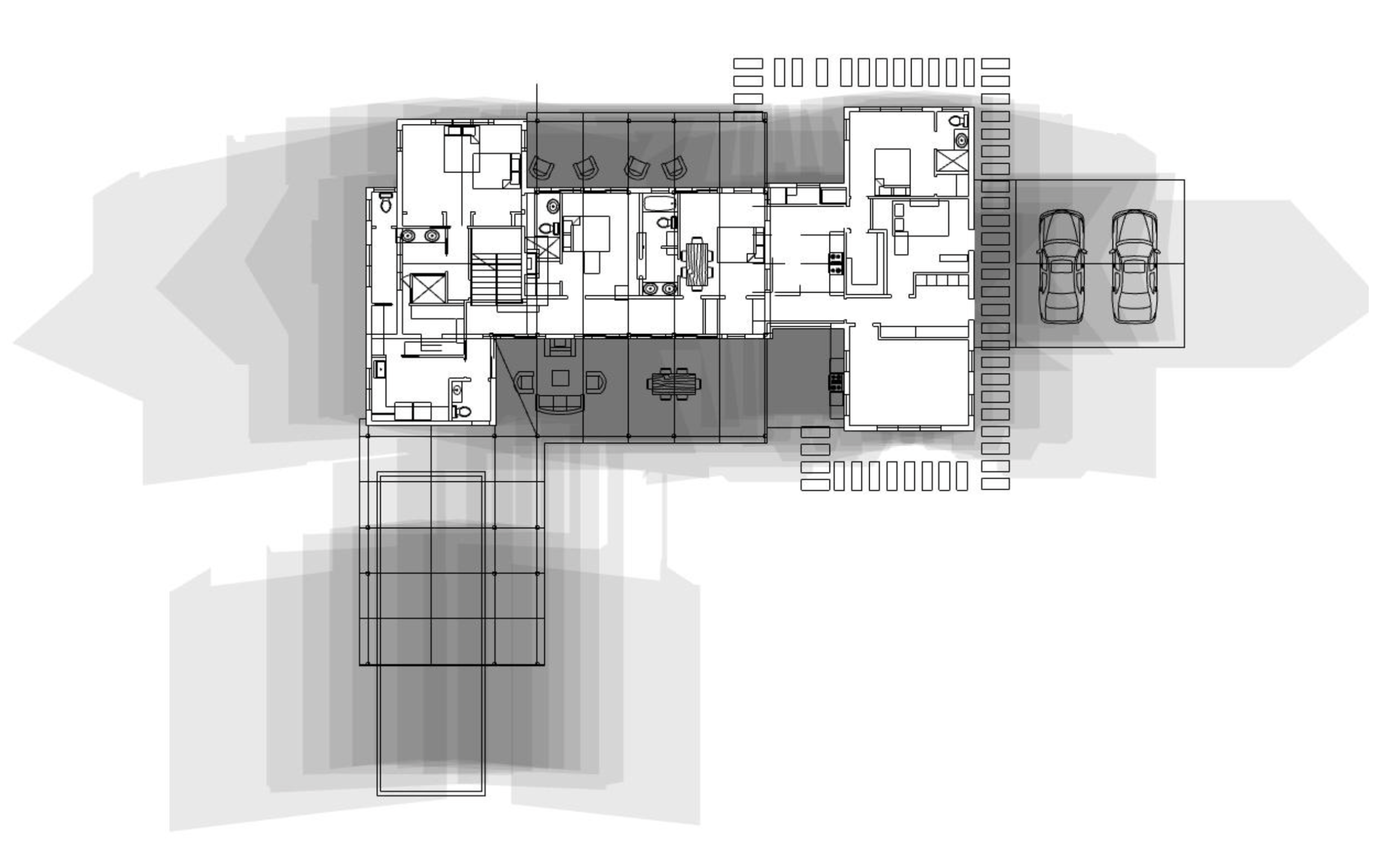

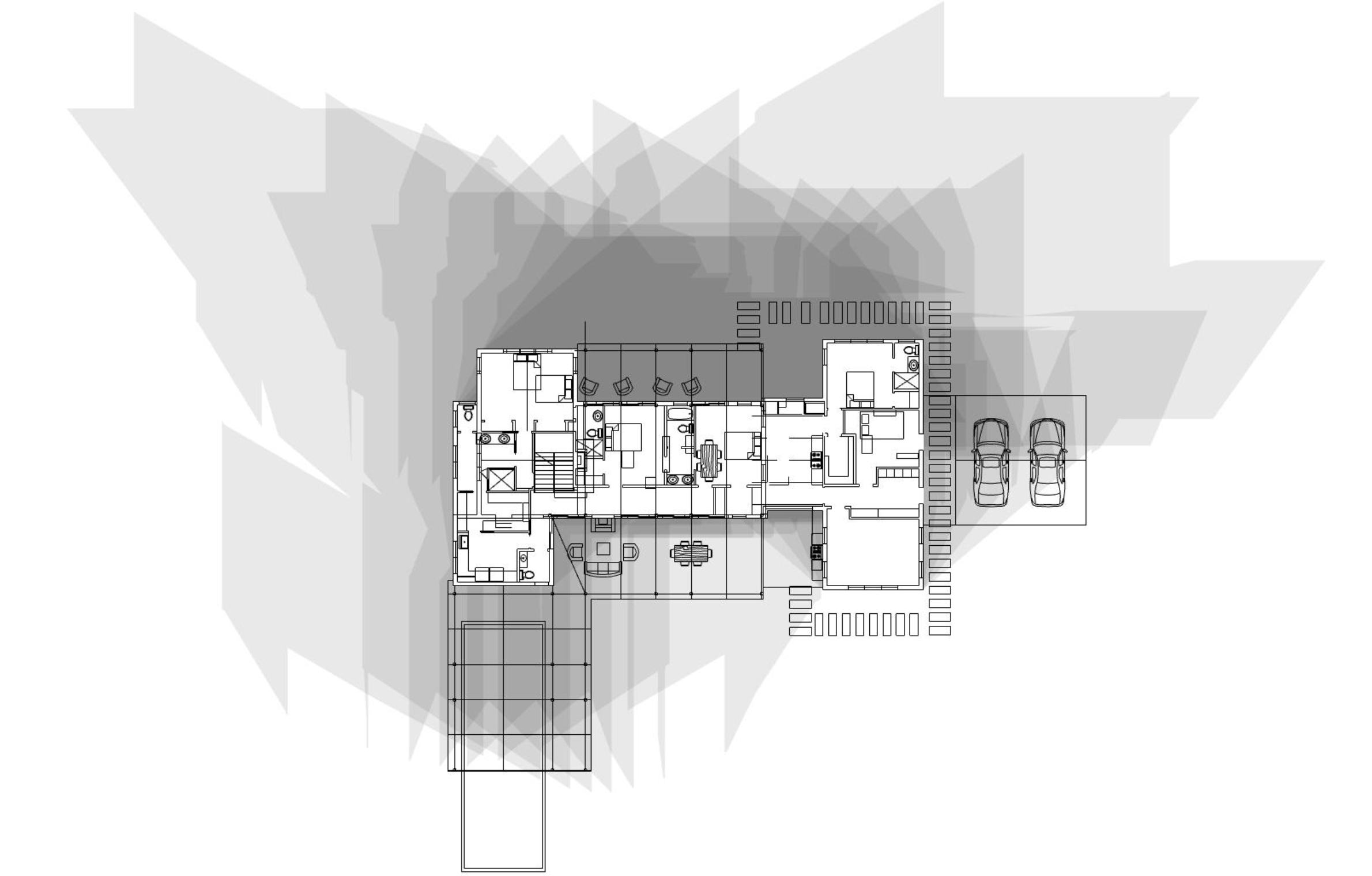

Take for example the seasonal shading analysis images below. Knowing how the building will shade its surrounding environment over the seasons empowers a designer to elementally play with light, as well as make informed choices for more comfortable outdoor living spaces. Combined with a through understanding of a given location’s outdoor comfort profile (see graph), this is a powerful analysis for a project that wants to leverage outdoor living spaces as a part of the program. This is just one way environmental design can provide powerful feedback while the design is still fluid so that changes are easily accommodated.

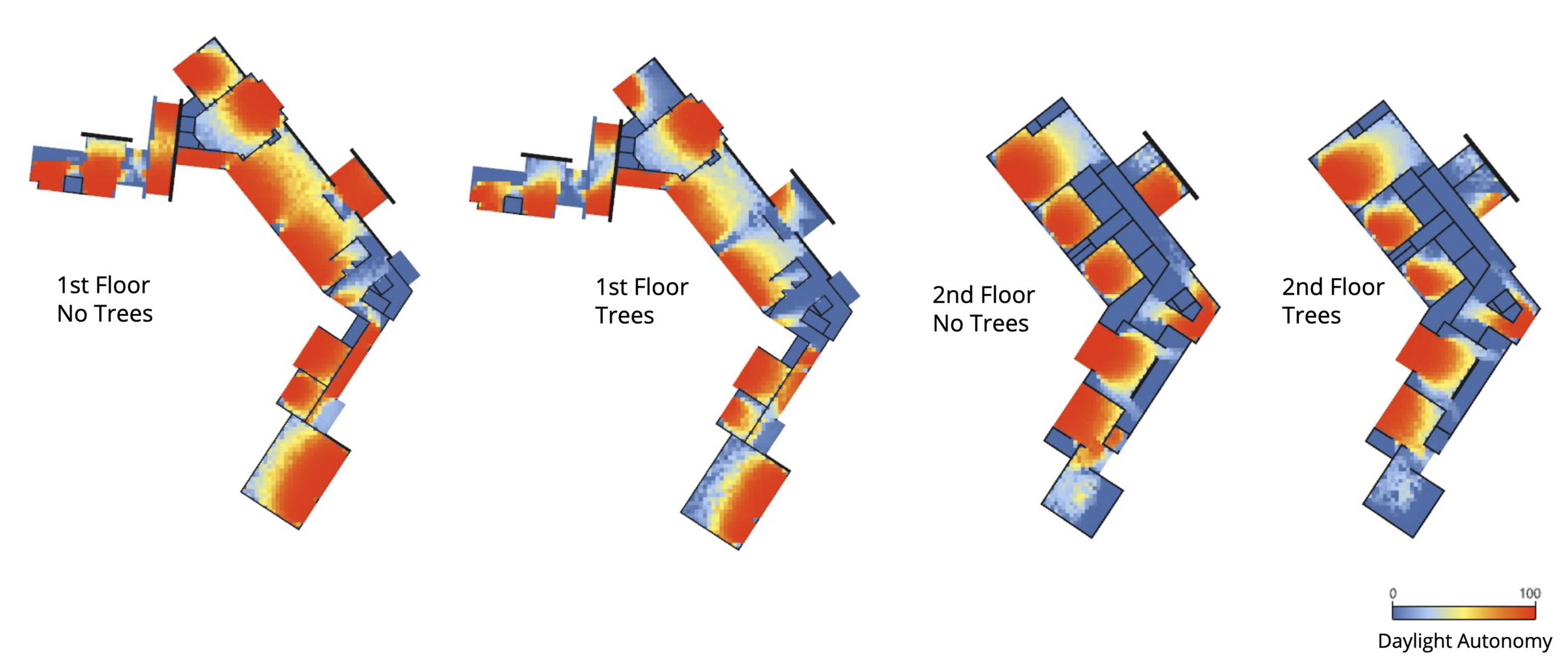

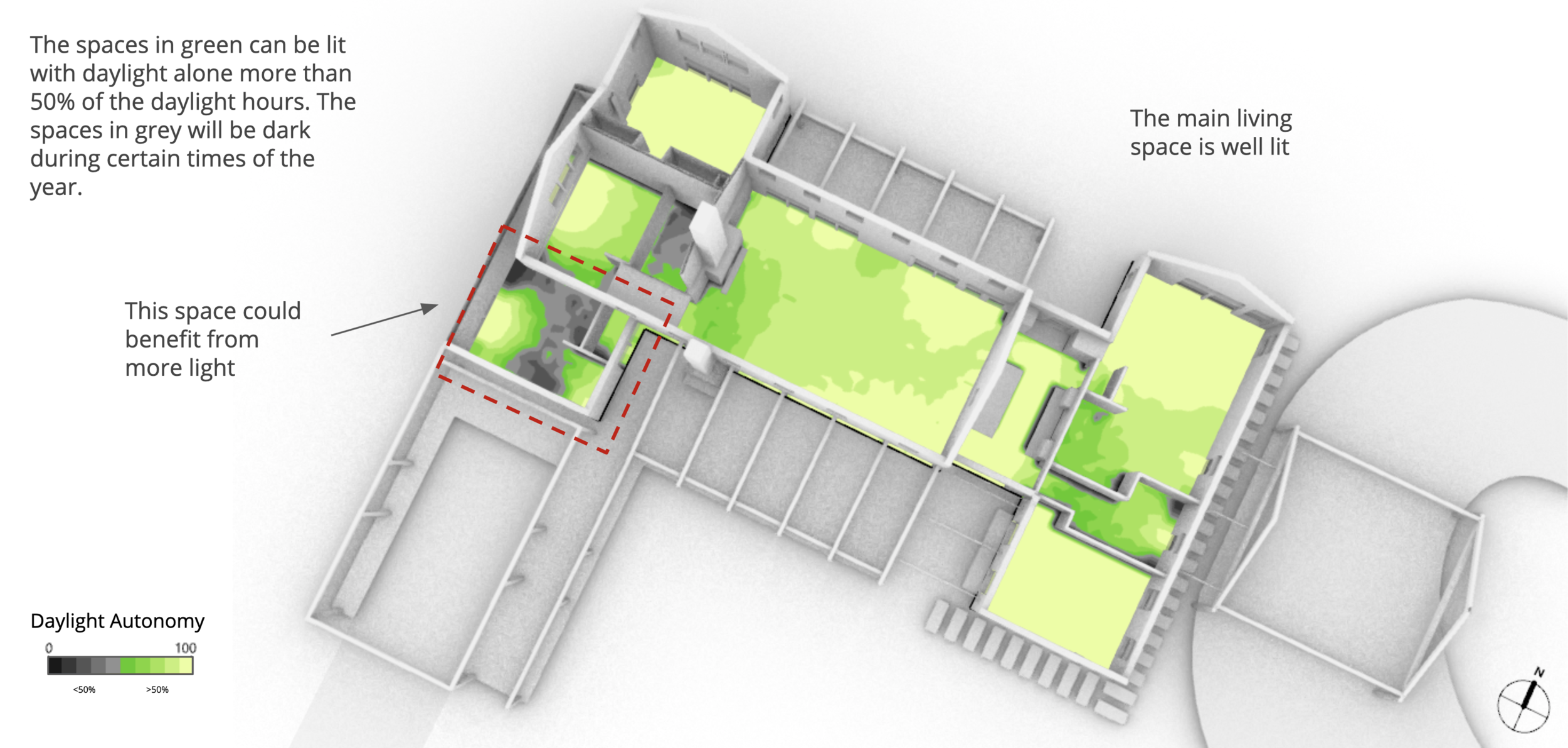

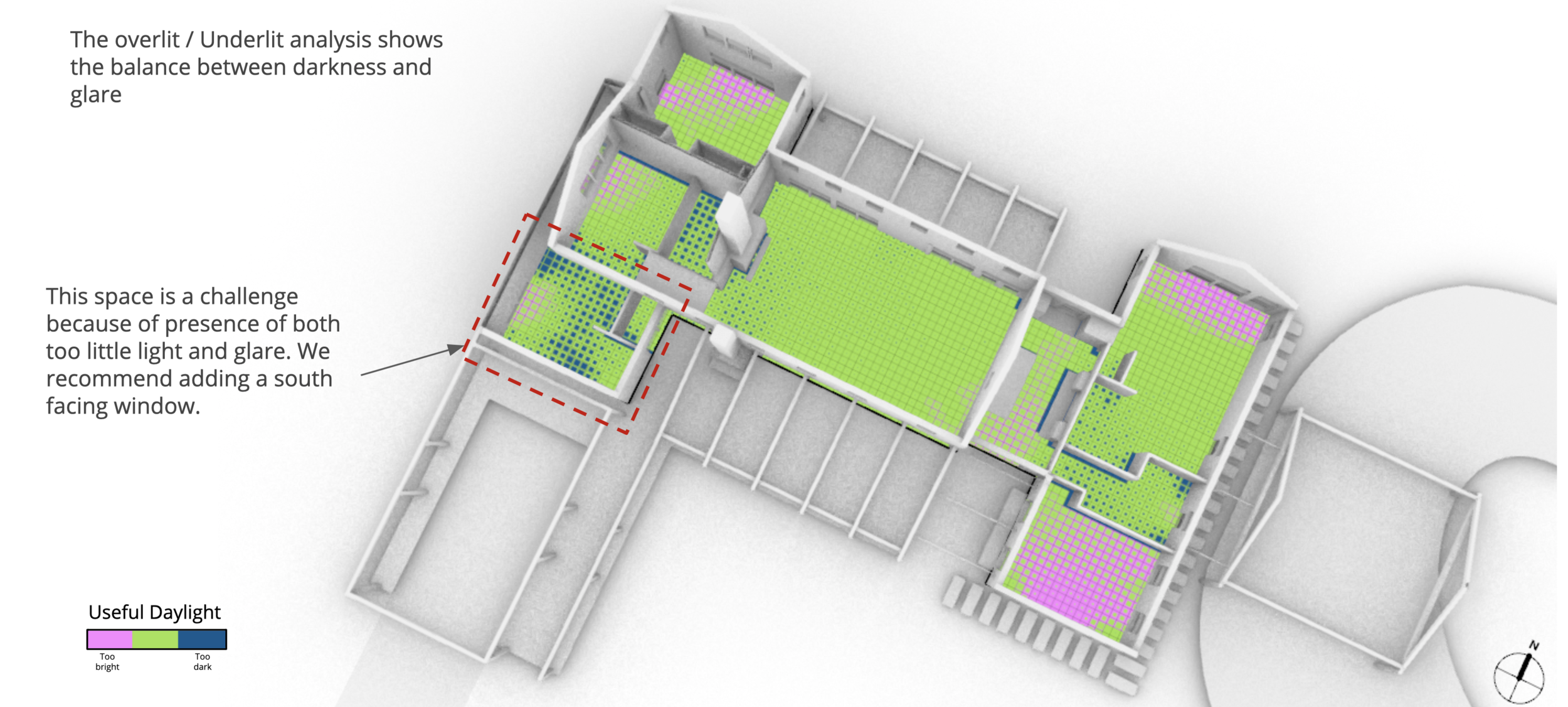

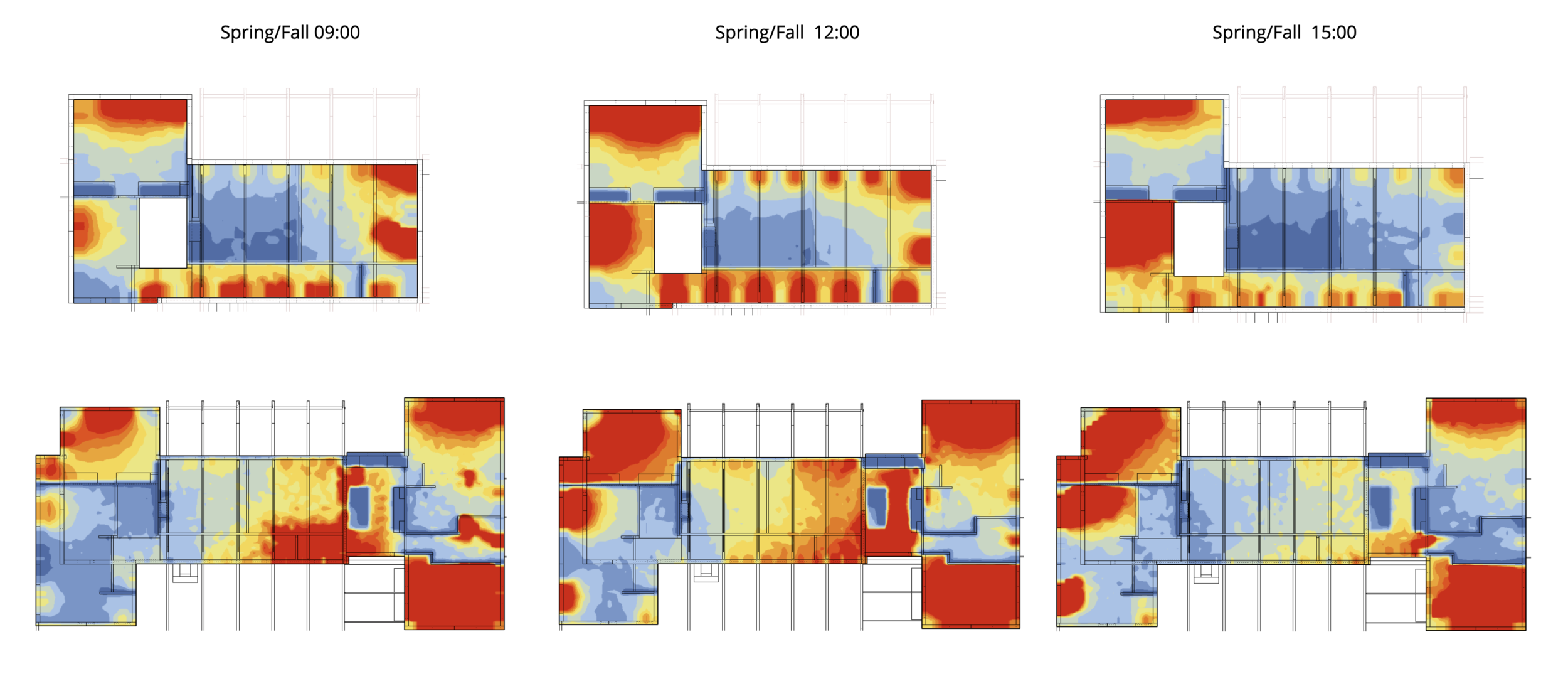

Another potent set of data to understand and visualize are daylight autonomy scenarios. We can evaluate how long a space can comfortably operate without electric lighting in these analyses in very detailed ways, accounting for trees and seasonal changes. In the images below, you’ll see a few examples of visualized daylighting scenarios expressing seasonal differences and accounting for autonomy, as well as glare. Improving a design’s ability to leverage usable daylight will improve the occupant’s visual comfort.

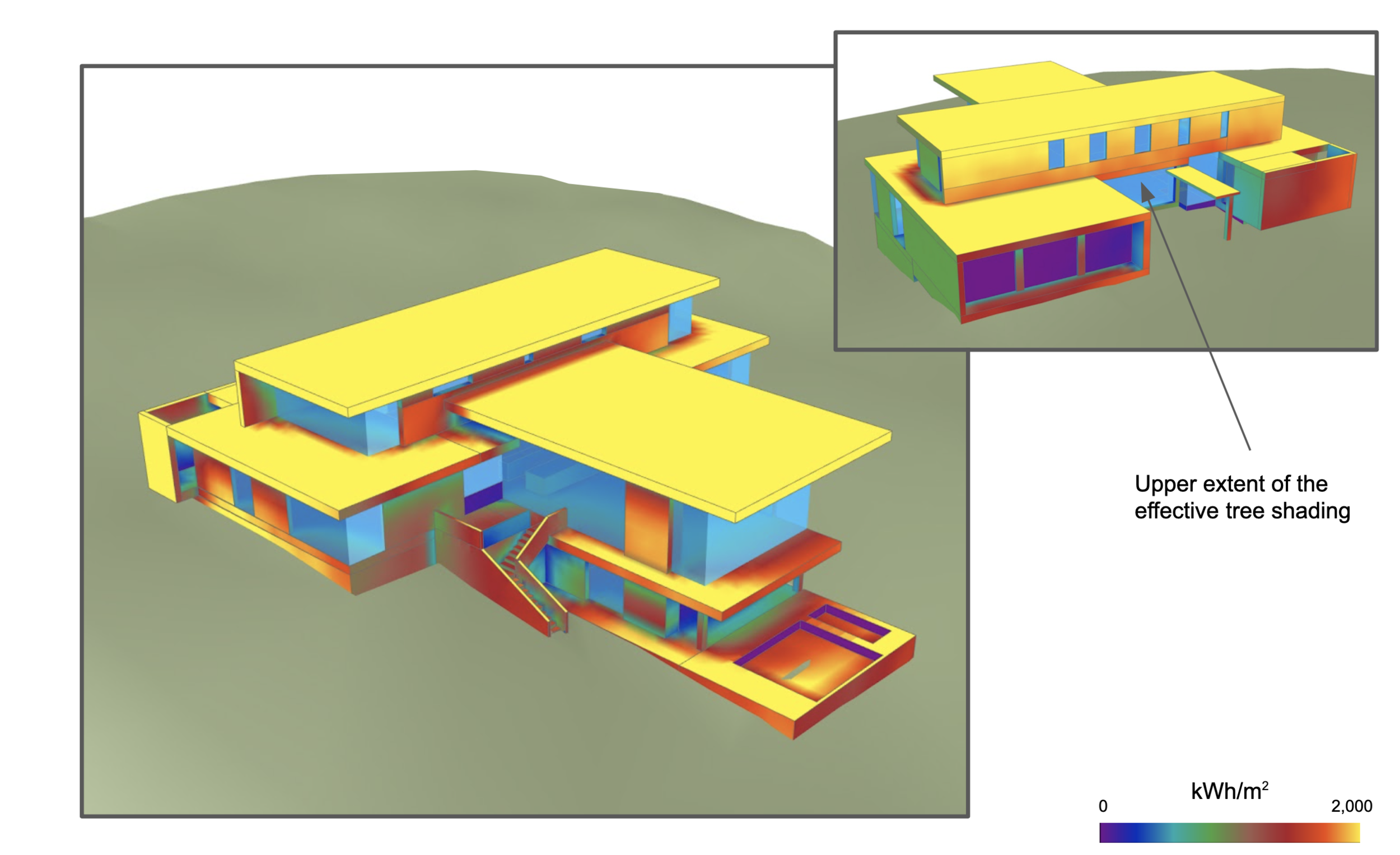

Heat

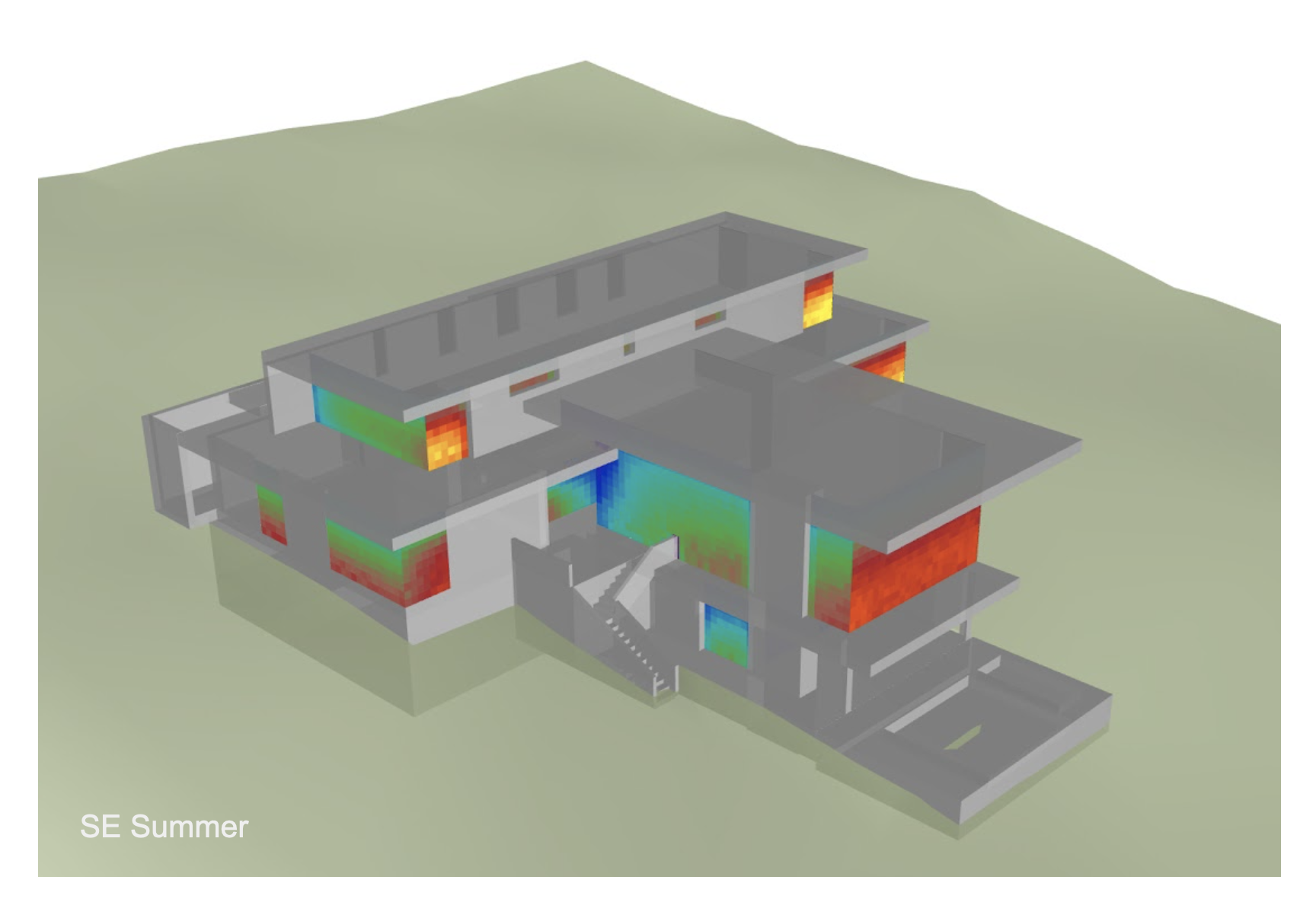

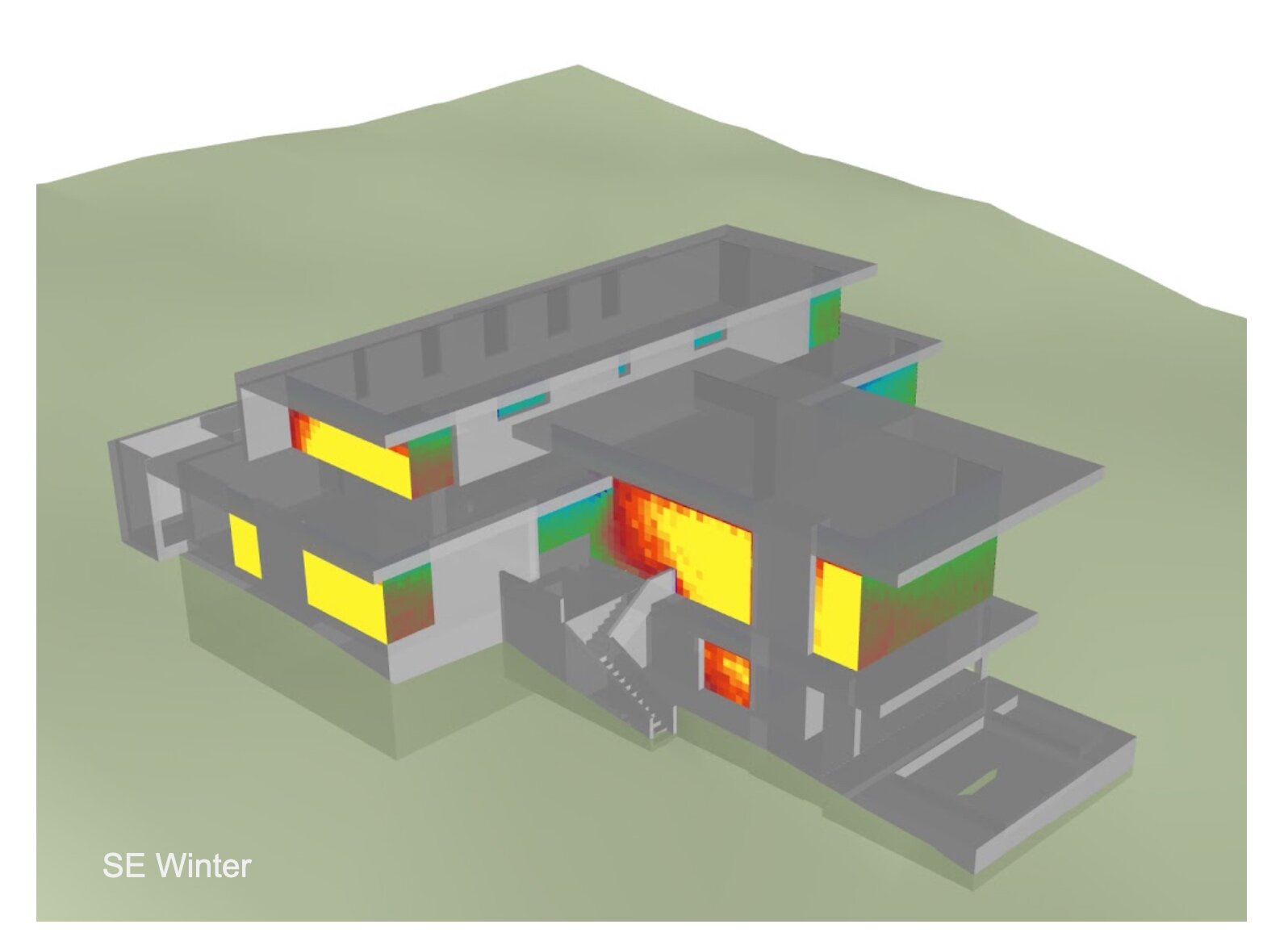

In the images below, you’re seeing an annual solar insolation study, which evaluates the architectural massing’s access to the sun. This information can inform window placement for either a winter solar heating strategy or to avoid heat gain in the summer. Self shading from the massing and shading from nearby buildings can be incorporated into various design strategies as well. Trees provide significant shading for the ground floors, but less benefit on the second floor and top of the great room.

Environmental design is a great tool to make optimum impact on window selection and placement as well.

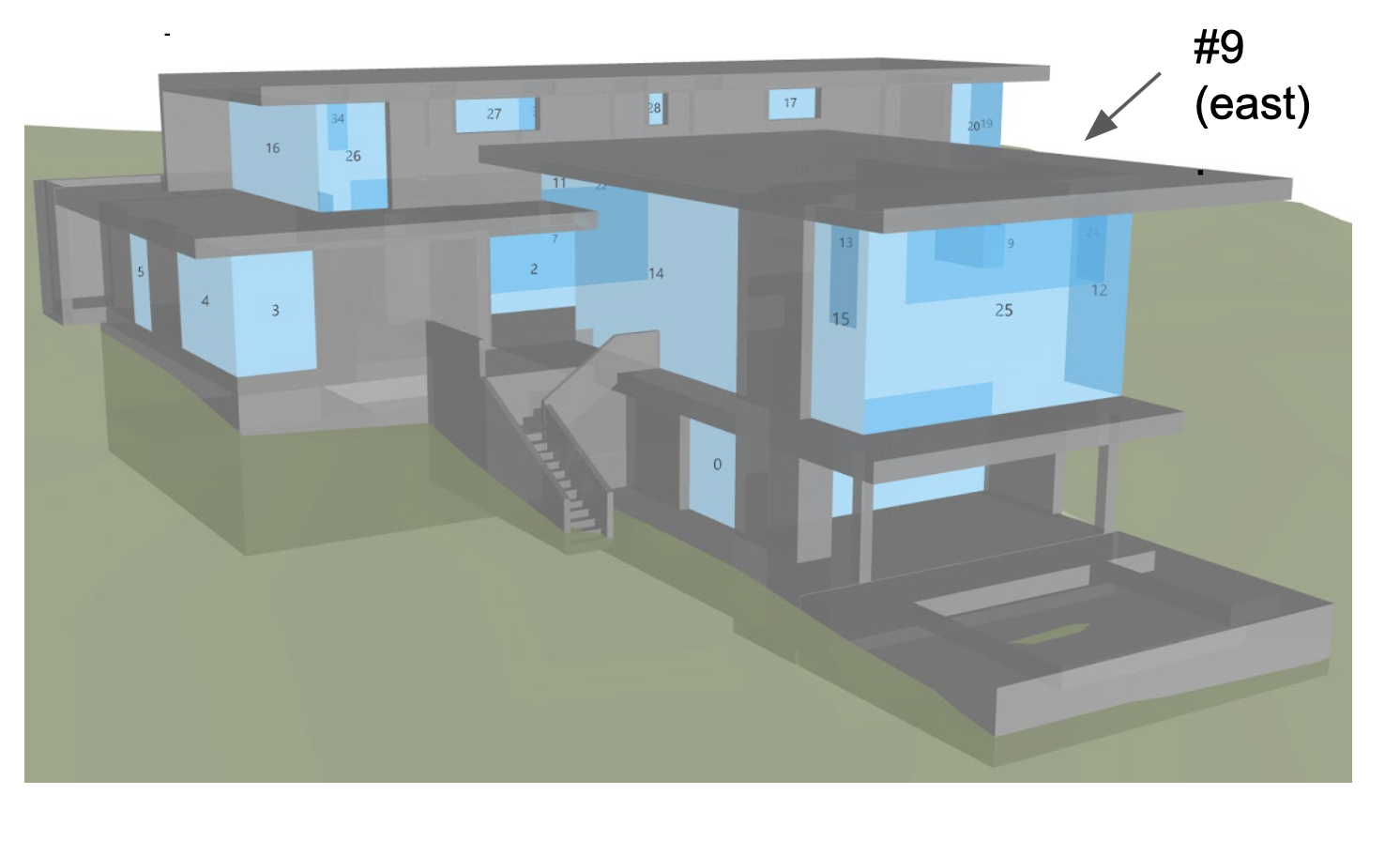

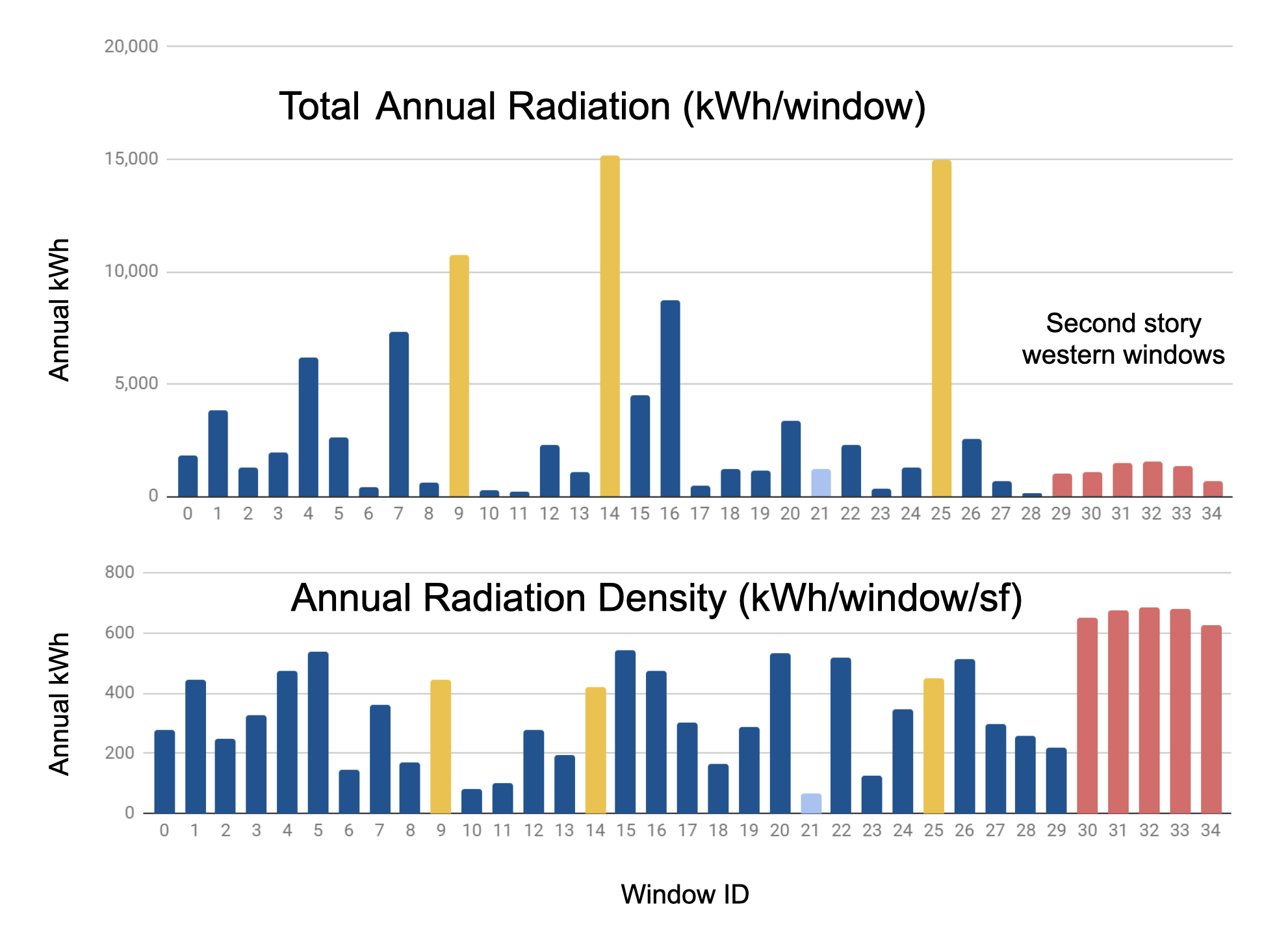

This kind of feedback is important because not all windows are created equal. The graphs in photo 2 show the annual heat gain contribution of each window. The three windows marked in yellow account for 39% of the total annual heat gain. The western facing windows on the second story are small, but also receive very direct solar energy in the summer. Boom - right there we can see some low hanging fruit to guide design decisions. From a thermal gain perspective, these windows could benefit from a reduction in size, and exterior shading strategy or a low SHGC film. Dealer’s choice.

What makes this kind of analysis useful is to get an early handle on potentially high thermal load contributing windows before the client has seen the concept and falls in love with the way things are. It’s a great time to identify strategies for thermal baseline improvement - like adding or extending overhangs, moving or re-sizing windows, etc. - without an unnecessary battle to “undo” something a client has already seen.

Window identification graphic used in conjunction with radiation and radiation density charts

Window radiation and radiation density charts used in conjunction with window identification graphic

Strategies

There are many other useful pieces of feedback that environmental design can highlight as well depending on the project.

We can look at enclosure details and performance (even benchmarked in comparison to multiple building standards).

We can look at healthy building materials.

We can look at embodied carbon.

We can look at natural ventilation potential.

We can compare massing performance in different rotation scenarios.

We can look at conceptual energy baselines, evaluating where improvements can be made across the entire building.

We can look at indoor air quality criteria.

We can look at future climate considerations.

The list goes on and on. All this to say that there are powerful tools often left on the table in the early stages of design that result in less than optimal outcomes down the road. We have the ability to shake this outdated paradigm and plug in data-driven decisions into the conceptual design process. That’s exactly what we’re here to help with - we just need to be engaged early enough to make a difference. But once the process is underway, the outcomes are all the proof any designer needs to make it a part of their process forever.